What do Carolyn Bessette-Kennedy's clothes really reveal?

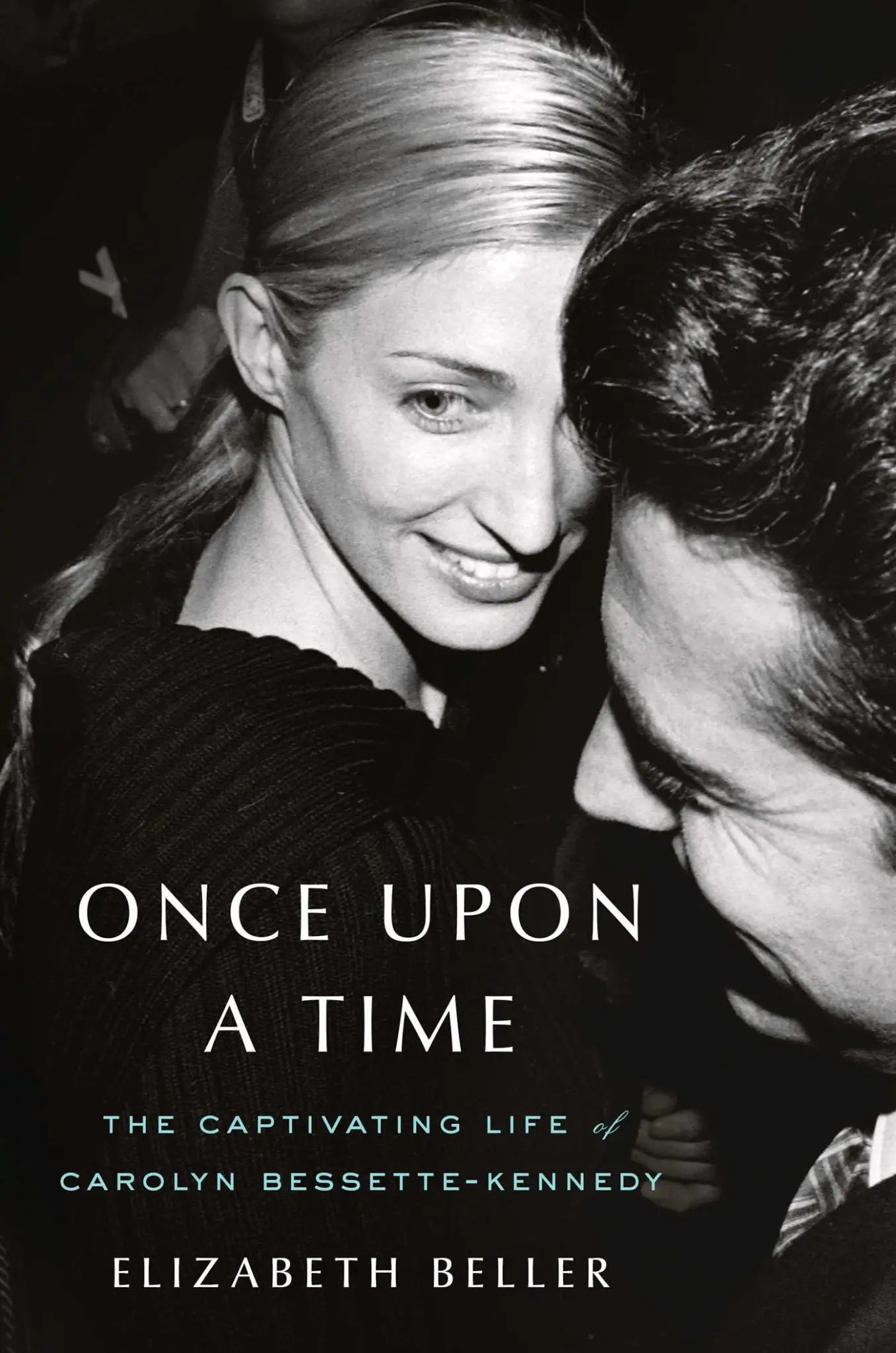

A new biography of the doomed fashion icon highlights the bizarre ritual of dressing for public consumption, and the tyranny of personal style.

One day last winter, I felt very depressed and went outside wearing sweatpants.

I chose an especially baggy pair — black, of course — along with an oversized black sweater. I strapped on a pair of big black lug sole boots, wrapped a big black scarf around my neck and topped off my ensemble with a big black parka. I pulled the coat’s enormous hood over my head.

At first I felt heavy and shapeless, unmoored, as a lumbered along the slushy sidewalks in my big, bulbous outfit. But then, I began to delight in this way of moving about the world, like an amorphous blob — invisible, my body and face erased. I could feel, with each step, a shedding of some kind of burdensome self: the one who is unduly vain and obsessed with appearances, the one who frets over every blemish accrued or pound gained, the one who constantly craves attention and validation. These selves melted away — briefly, temporarily — and for that moment, at my most bedraggled and unattractive, I felt absolutely free.

I kept thinking about this moment while reading “Once Upon a Time: The Captivating Life of Carolyn Bessette-Kennedy,” which I wrote about for The New York Post. Bessette could never experience that kind of blissful anonymity, at least not after she hooked up with “America’s prince” John F. Kennedy Jr.

The biography, by Elizabeth Beller, aims to paint a more “nuanced” portrait of the 1990s “it girl,” who died at 33 in a plane crash off the coast of Martha’s Vineyard with husband and sister Lauren. In truth, it’s a bit more airbrushed than nuanced; Beller works hard to convince us that Carolyn was nice, actually.

Yet, Beller unspools a dark fairy tale in which “an ordinary person” falls in love with “America’s prince,” the son of President JFK and First Lady Jackie — and then pays the price.

She was pilloried by the press. Paparazzi parked outside the pair’s Tribeca apartment, hounding her as stepped out onto the sidewalk, snapping her minimalist chic ensembles, which she (almost) always paired with a scowl. Yet after her untimely death, these photos remain, enshrining her as a fashion plate. Her outfits, nearly 25 years later, still generate frenzy and desire. Just look at the dozen or so Instagram accounts devoted to pictures of her.

Beller wonders if Bessette’s enviable hauteur, her simple black sheath dresses, camel car coats, and white button-downs weren’t an expression of her exquisite, pared-back taste, but of her self-effacement. After all, she argues, before she seriously dated “John John,” she let her unruly, pre-Ralphaelite mane go wild; she paired her Calvin Klein bias-cut silk skirts with sneakers; she had darker, fuller eyebrows. Beller writes:

Her wardrobe was a way to further shield herself (more than just, as recently speculated, “a way to have a conversation with the public”). Her go-to choice of Yohji Yamamoto was a defensive measure, with the designer describing his work: ‘I make clothing like armour. I wanted to protect the clothes themselves from fashion, and at the same time protect the woman’s body from something.’ Nothing could have suited her better at the time. …

“She became obsessed with not giving the press anything to find wrong — a hair out of place, the wrong color or fit of clothes, or having a scrap of direct under er fingernails — and obsessed with trying to control it,” said a close friend. There was a muting of herself — in her hair, body style of dress — to make herself less remarkable, less accessible, less newsworthy, both to the press and to the public, who were hounding her in increasingly intimidating ways.

I don’t entirely agree with this: most people do tend to tone down their style in their 30s, and it wasn’t like Bessette dressed like a full-on bohemian in her 20s (she worked at Calvin Klein, after all). But there is something singularly blank about Bessette’s signature aesthetic — how it’s truly timeless in a way that she could be of any era, much more so than other forever “fashion icons.” Jackie O followed Parisian fashion a little too slavishly. Princess Di had a more playful, pointed approach to dressing. Even Audrey Hepburn, the paragon of so-called “timeless” chic, so thoroughly embodied the 1960s. Yet, rather than a ploy to make herself less remarkable, Bessette’s severe wardrobe comes across as the opposite: to prove her extraordinariness. After all, what better way to stand out than by outshining everyone while wearing the most neutral, unextraordinary threads? (Choosing stuff from Prada and Yamamoto, two great designers who can coax poetry out of the most humble materials, like nylon, or the most neutral colors like black, certainly helped.)

Still, there is something to this idea of this clothing as “armor.” You could argue that getting dressed as a woman, particularly in New York City, where you don’t have the luxury of hiding in a car, where you are always exposed, particularly to the male gaze, is something like getting suited up for battle. Sometimes, we get dressed not to attract attention or even express ourselves, but to simply say GO AWAY, NOTHING TO SEE HERE.

I thought about the way public figures dress, how we study their clothes for clues about who they are or for messages about what they’re trying to communicate to us. You see this with Taylor Swift, with Beyoncé, and recently with Cate Blanchett, who recently donned a dress black, green, and pale pink dress on the Cannes red carpet that fans read as a statement in support of Palestine. Yet, can clothes really truly reveal our hearts, our souls, our desires, our beliefs, our lives? The Instagram accounts scrutinizing Bessette’s images think so, but it’s not really so simple.

Many years ago, the Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology mounted an exhibit devoted to the socialite Daphne Guinness, an eccentric clotheshorse known for her extreme, spiky couture. Here’s what I wrote at the time:

At the press preview for the exhibition, Guinness — shy, with a quavering voice — insisted that the exhibition was not about her, but about the clothes, about the art and craft of fashion. … [And] she was partly right: We can't get to know the real Daphne Guinness through her clothes. After all, you can glean all sorts of information from someone's clothes — her socio-economic position, her aesthetic preferences — but you can't know her or her heart or fears or even her personality. Guinness' clothes command all our attention, allowing her true self to hide behind them.

There is a section of the exhibition devoted to "armor," featuring Guinness' more warrior-like pieces, including a bodysuit by the young British designer Gareth Pugh completely covered in nails. The wall text includes a quote by Guinness: "I think it's beautiful to be able to cover yourself in metal. I love the color and the way it reflects. But it is also a protection." We so often assume that an interest in fashion is a sign of vanity, but in fact it can be the opposite: a result of shyness or a lack of self-confidence. It also allows the wearer a chance to transform into a different person.

Daphne Guinness despite its shortcomings -- or maybe even because of them -- presents an intriguing concept of personal style: that it isn't just a means of self-expression, but of disguise and evasion. Maybe even of negation.

I loved this

Great piece!!