Rosamund Pike Knows How to Dress the Part

The 'Saltburn' actress's veiled Golden Globes ensemble recalled the way old film stars like Marlene Dietrich used fashion to craft their larger-than-life personas both on and off the screen.

Rosamund Pike arrived at the Golden Globes this past Sunday like a fabulous, slightly evil matriarch of a rich dynasty attending her murdered husband’s funeral. The Saltburn actress wore a tea-length black-lace Dior frock with fishnet sleeves, black pumps, and — le pièce de résistance — a matching headpiece and netted veil by celebrated milliner Philip Treacy.

When asked about her unusual topper, Pike revealed she had smashed up her face in a ski accident over the holidays. Her bruising had healed in time for the event, but she had already commissioned the veil and decided to wear it anyway. “I kind of fell in love with the look,” she said.

The look is pure Pike: beautiful … but off. She’s the queen of dressing like the main character in a way-more interesting plot than the ones she typically finds herself in: an awful Golden Globes ceremony, a dull BAFTA tea.

Early in her career Pike was positioned as an English Rose type — blonde and fair, she played both a Bond Girl and a Jane Austen character. Back then, she wore more traditional ingenue fare: tight LBDs, slinky silk gowns, strapless party frocks. But in but in the past decade or so Pike (working with stylist Leith Clark) has leaned toward a kind dangerous glamour. Some of her most deliciously deranged outfits include a puffer dress worn with a beaded face veil, a hooded sci-fi gown, an enormous red tulle Molly Godard frock paired with lug-sole boots (and a kind of demented smile).

Pike’s offbeat red carpet ensembles compliment the characters she tends to play. Think Saltburn’s decadent matriarch, or Gone Girl’s sociopathic femme fatale. Pike is conventionally attractive, but she has a destabilizing presence on screen, and she taps into this tension in the way she dresses in her public life, too.

Pike’s devotion to playing the part 24/7 reminds me of some of my favorite Old Hollywood icons — personae like Katharine Hepburn, Liz Taylor, Joan Crawford, and most of all Marlene Dietrich.

Dietrich was the ultimate image architect, far more of an auteur than any of the men who directed her. A recent show at the International Center of Photography explored this. “Marlene Dietrich: Play the Part,” which closed earlier this month, traced the evolution of this singular artist’s persona through a trove of 250 images, examining how Dietrich constructed her own image of independent, fearless glamour.

Dietrich was born in Berlin and started out as a theater and silent film actress in Germany. As a young ingenue, she would practice posing in a photo booth, experimenting with lighting and angles to figure out how she looked the most dramatic. (In silent film, the close-up is everything.) It was there, the exhibit asserts, that Dietrich discovered her “signature lighting”: one single spotlight that would not only sculpt her cheekbones but create a halo effect over her blonde hair. No matter what director or photographer Dietrich worked with, she made sure they lit her like that. (Dietrich walked so Barbra Streisand could run, I guess!)

Nowadays, we would say that Dietrich made sexuality — or more precisely, bisexuality — her “brand.” She catapulted to fame in 1930 with The Blue Angel, a German film about an amoral cabaret performer who drives a middle-age schoolteacher to ruin. That same year she decamped to the U.S. and made her Hollywood debut in Morocco as a world-weary nightclub singer. In a notorious scene, Dietrich performs in a tuxedo and top hat and kisses another woman on the lips, arousing both the men and women in the audience. Incredibly, the publicity for the film did not shy away from its gay undertones. The tagline: “The woman all women want to see.”

Dietrich frequently played sexually adventurous, liberated woman, and she played this up off screen by wearing traditionally “male” garments: trousers, ties, button-downs, and suit jackets, which she paired with luxurious furs and jaunty berets. Unlike Katharine Hepburn, who also defiantly donned trousers (a not-insignificant transgression in the 1930s), Dietrich didn’t just like trousers for comfort and practicality, but also for their power to provoke and titillate. That she wore them with arched pencil-thin eyebrows, obviously painted face, glossy wavy hair, and her sultry lidded eyes gave her suits an added sexual frisson.

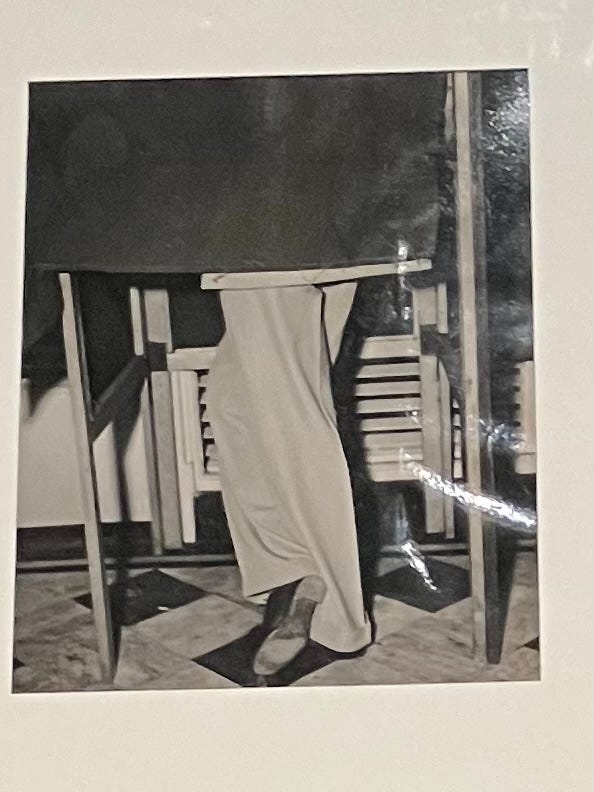

Dietrich renounced her German citizenship during World War II, and she had a photographer take a photo of her casting her first vote as an American. She’s behind a curtain, but you know it’s her from the the casually crossed feet, the capacious trouser legs, the worn but elegant brogues. It was so Dietrich, and also so against everything that Nazi Germany and Hitler stood for. It was masterful image-making — perfectly setting up Dietrich’s next stage, as a performer for the Allied troops and defender of freedom, of all types.

In 1960, the Observer published an article about Dietrich’s style. The actress, then 58, arrived to the interview wearing “a wild mink coat; a black Balenciaga dress embroidered, at the left breast, with the scarlet bar of the Légion d'honneur; a stiffened black tulle hat; white kid gloves; black patent leather pumps; and a black crocodile handbag.” When asked about her “wardrobe secrets” she summed up her approach to fashion as a public figure, its power to communicate an image or ideal, and the idea of “dressing the part.”

"I dress for the image," she announced. "Not for myself, not for the public, not for fashion, not for men." The image? "A conglomerate of all the parts I've ever played on the screen. When I was in The Blue Angel people thought that was me: they really thought that was me!

"If I dressed for myself I wouldn't bother at all. Clothes bore me. I'd wear jeans. I adore jeans. I get them in a public store – men's, of course; I can't wear women's trousers. But I dress for the profession.”