Dreams On Sale: Rose Hartman captures the mysterious allure of the shop window

The event photographer, like so many before her, turns her lens toward the glamorous mannequins on the other side of the glass.

Yesterday, I walked by Bergdorf’s to admire its glittering holiday window display, and thought of this essay I wrote. It was supposed to be for a book of the photographer Rose Hartman’s images of shop windows that never materialized, so I’m publishing it now. (This is a long one, with lots of images, so your email may not display the whole thing, so just click on the headline and go straight to the post.) Happy Holidays!

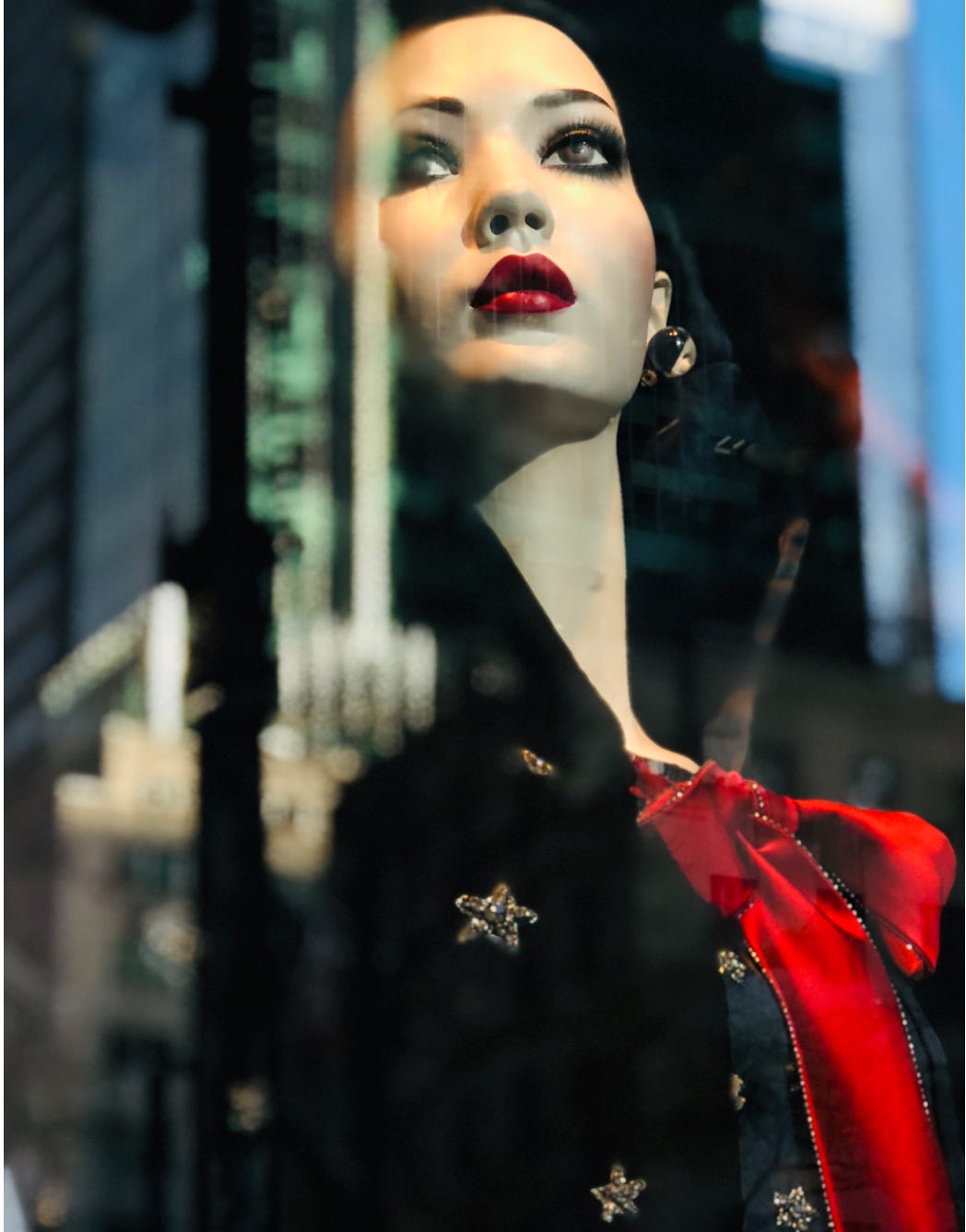

A beautiful woman. Jet-black hair, slate-gray eyes, long lashes, arched brows. She has pillowy scarlet lips, porcelain skin. She wears a plush black jacket embroidered with glittering stars and tied closed with a red ribbon. She gazes up, somewhere beyond the tall towers and city lights reflected in the window in front of her. Is she hopeful? Desperate? In love? Heartbroken?

Her glamorous inscrutability evokes the mystery of an Edward Hopper heroine — the lonely usher in the painter’s “New York Movie,” perhaps — or one of Douglas Sirk’s exquisitely suffering housewives. Or maybe Gene Tierny’s dressed-to-the-hilt sociopathic socialite in the technicolor noir Leave Her to Heaven.

Upon closer inspection, however, this woman is not a woman at all. She’s a mannequin, looking out the window of a high-end Manhattan department store, luring shoppers inside with her sparkling clothes and manufactured perfection. You, too, can have this, she seems to whisper to us plebes out on the sidewalk looking in. You, too, can have this wardrobe, this beauty, this whatever-it-is that you, on the other side of the window, out in the cold, want.

It’s a tantalizing photograph, full of romance and ambiguity and longing. I can’t think of another picture of a mannequin that makes its subject appear so plainly stunning, instead of unsettling or grotesque or cheesy. And I can’t think of anyone else but Rose Hartman who could have taken it.

Hartman has an eye for beauty. A veteran party photographer, she has made a career chronicling “the beautiful people” at their most beautiful: Bianca Jagger on a white horse, Cindy Crawford and Naomi Campbell dripping in jewels, David Bowie and Iman looking like the gods we imagine — hope — them to be.

She hunts for beauty outside the rarefied fashion world, too. After photographing a fancy gala in the 1980s and ‘90s, she often traipsed downtown to the Palladium or Mudd Club, where she encountered a different sort of crowd. In these spaces, she scoped out New York City’s radiant children in crazy, out-there outfits: a gal in a leotard carrying a Peanuts lunchbox, for example. She made these kids shine as brightly as the couture-clad stars she orbited at fashion shows and charity balls and Studio 54.

One afternoon, in 2019, Hartman was strolling through midtown Manhattan — her antenna, as always, attuned to the city’s charms and surprises — when a particularly alluring figure standing alone in the window at Saks Fifth Avenue made her stop.

“She looked like Catherine Zeta-Jones,” Hartman said of the mannequin who caught her eye. “She looked quite striking.” She whipped out her iPhone and took a picture.

Soon, she was snapping photos of mannequins throughout the city — at the big department stores, at Ralph Lauren on Madison Avenue, even in some small boutiques downtown. Some had painted, lifelike faces. Some had no faces and shiny bald heads. Some posed on fancy upholstered seats under red lights, and some stood in front of modern, geometric backdrops. She took pictures of mannequins during her travels, as well (Paris, Mallorca), but they lacked the razzle-dazzle and attitude of the ones in her hometown. Something about the buzz and energy surrounding the windows in the Big Apple — with its whooshing taxi cabs, blinking lights, and pavement-pounders reflected in the glass — made the New York pictures uniquely ALIVE. They vibrated with excitement, ingenuity, and motion, even if the subjects were lifeless.

But then, if you have ever met Rose Hartman, you know she’s incapable of taking a lifeless photo.

Hartman — petite, blunt, with spiky hair to match her spiky attitude — grew up in 1940s New York City, in a sixth-floor walk-up in rough-and-tumble Alphabet City. Despite her unglamorous environs, she was surrounded by elegance. Her father, an enthusiastic amateur photographer, designed costume jewelry. Her mother taught elementary school, subscribed to Vogue, and made sure she and her daughter were always turned out. In the intro to her book, Incomparable Couples, from 2015, Hartman described their dazzling outfits:

Draped velvet dresses with matching hats, marcasite jewelry, even long gloves were my mother’s favorite attire when we went for Sunday dinner with our relatives who, generously enough, showered me with beautiful clothes. To this day, I remember taking a pony ride in Central Park, dressed in a tartan plaid skirt, jaunty cap and lace-collared blouse.

Hartman, a bright student, attended the prestigious Hunter High School uptown, where she rubbed shoulders with the children of Manhattan’s elite. Some of her classmates wore real pearls and cashmere sweaters to school. Hartman was enthralled. “I said to myself, ‘That is the way to dress,’” she told me some six decades later. “But I wouldn’t have known that if I had stayed in the East Village.”

After college, Hartman taught high school English for a few years on the Lower East Side, in a building that looked “like a prison.” She longed for a more exciting life — the kind her moneyed former classmates enjoyed, the kind she saw in the society pages of Vogue magazine. One day, a boyfriend asked her what she enjoyed doing. She thought of her father with his omnipresent camera. She thought of the “thousands of hours” she spent pouring over Helmut Newton’s seductive fashion photos in Vogue or Brassaï’s scintillating shots of 1920s Paris. She told him she would like to take pictures.

In the summer of 1976, she lucked into her first professional assignment: shooting Joan Hemingway’s extravagant society wedding in Sun Valley, Idaho, for the fashion trade publication DNR. (Hartman happened to be nearby, taking a photography workshop.) The bride wore Dior.

“It was my first entrance into the same world that was a mainstay of Vogue’s lifestyle pages,” Hartman wrote of the experience in Incomparable Couples. “Striking, sylphlike women and stylish men were my willing subjects. … I knew then that I wanted to chronicle the world of beauty, style, and celebrity.”

That outsider’s thrill to “beauty, style, and celebrity” distinguishes Hartman’s event photos. She has a photojournalist’s wits, an instinct for what the great Henri Cartier-Bresson called “the decisive moment.” Yet her pictures teem with wonder and desire. She can push her way through a crowd like the most tenacious paparazzo — and as a 5-foot-2-inch-tall woman among a sea of male shutterbugs she certainly has had to — but she doesn’t share Ron Galella’s glee at taking the famous down a peg with an unflattering snap. She’s never forgotten the little girl who devoured her mother’s Vogues and marveled at her classmates’ pearls.

Hartman brings that same wonder to her mannequin photos. She delights in the sassiness of a glossy white model in a disco-ball-like shift, the tackiness of a pop-art Marilyn Monroe head with an articulated robot hand, the cartoonish hauteur of a long-lashed bob-haired sylph. She relishes in the stuff they’re selling, too: sequined purses, slinky bias-cut silk gowns, crisp button-down shirts, city-slicker coats, oversized sunglasses, and big honking jewels — as well as all those less tangible things, like sex, self-confidence, youth, sophistication, cool.

This aspect of the shop window — its siren song promising happiness and self improvement, as well as its aesthetic beauty — has beguiled photographers since the dawn of photography. Rachel Bowlby wrote about this tension in her fascinating treatise on mannequins and modernism, Just Looking:

Consumer culture transforms the narcissistic mirror into a shop window, the glass which reflects an idealized image of the woman (or man) who stands before it, in the form of the model she could buy or become. Through the glass, the woman sees what she wants and what she wants to be.

Even before camera technology evolved to the point where it could successfully capture an image through glass, early photographers used trickery to replicate the look of a shop window. In 1843, pioneering lensman Henry Fox Talbot badly wanted to photograph a fetching window display at his local milliner’s shop, even though the long exposure time required to capture an image behind glass made it impossible. So, he faked it. Talbot set up shelves in front of a black cloth outside — those early cameras required a lot of light — and arranged a series of dainty ladies’ lace and straw bonnets on them.

Talbot’s “The Milliner’s Window” was a stunning facsimile — and not only because it looked like the real thing. The picture, with its exquisite rows of darling caps, evoked the strange pull a well-appointed window display can have. It was the first of a long line of photos that would try to document, understand, and in some cases puncture the allure of the shop window.

According to Karen Hellman, author of The Window in Photographs, early photographers took so many pictures of shop windows partly out of practicality. The first cameras were large and cumbersome, and took a long time to set up. Even by the mid-19th century — when exposure times had shortened considerably, from twenty minutes to about twenty seconds — portrait-sitters had to stay still for a significant amount of time while the camera worked its magic. (Photographers sometimes put children in restraints to keep them from squirming!) Shop displays and their mannequins proved much more forgiving subjects.

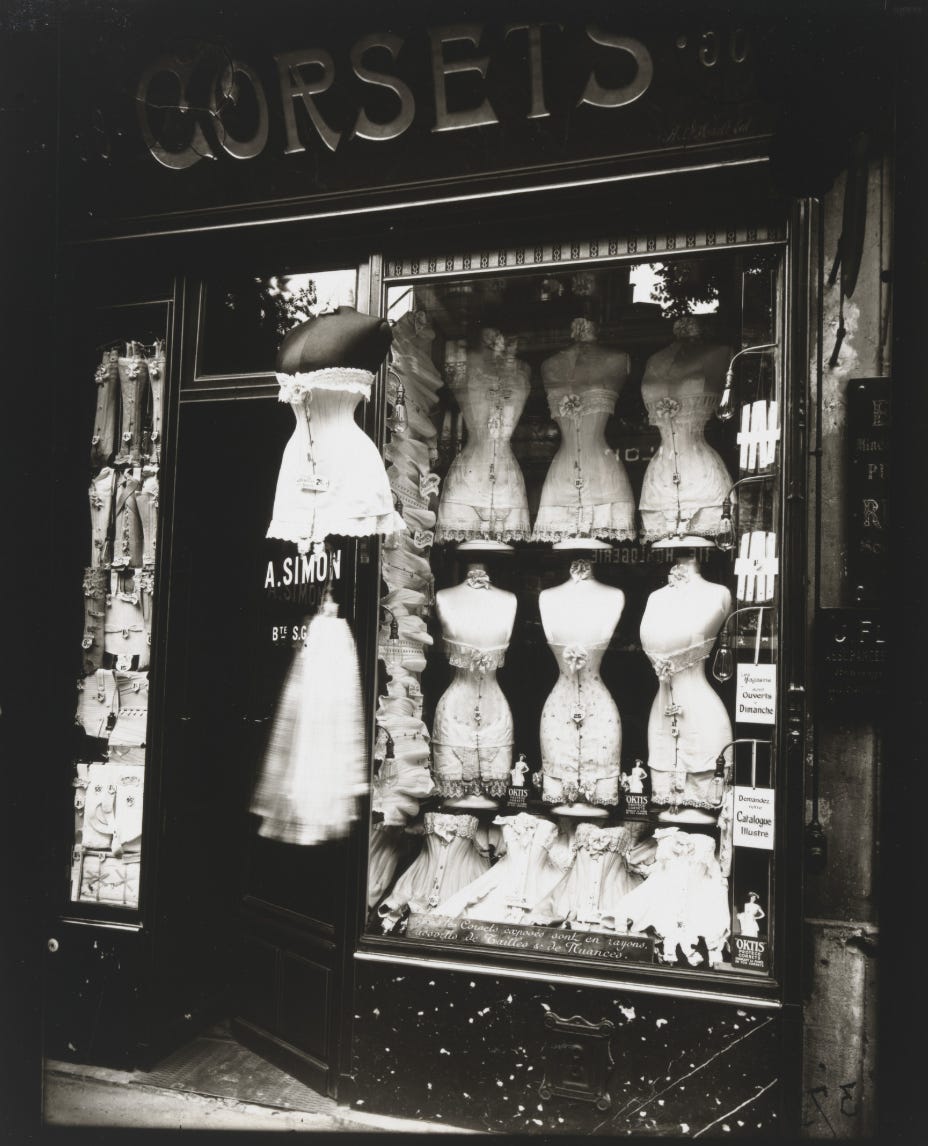

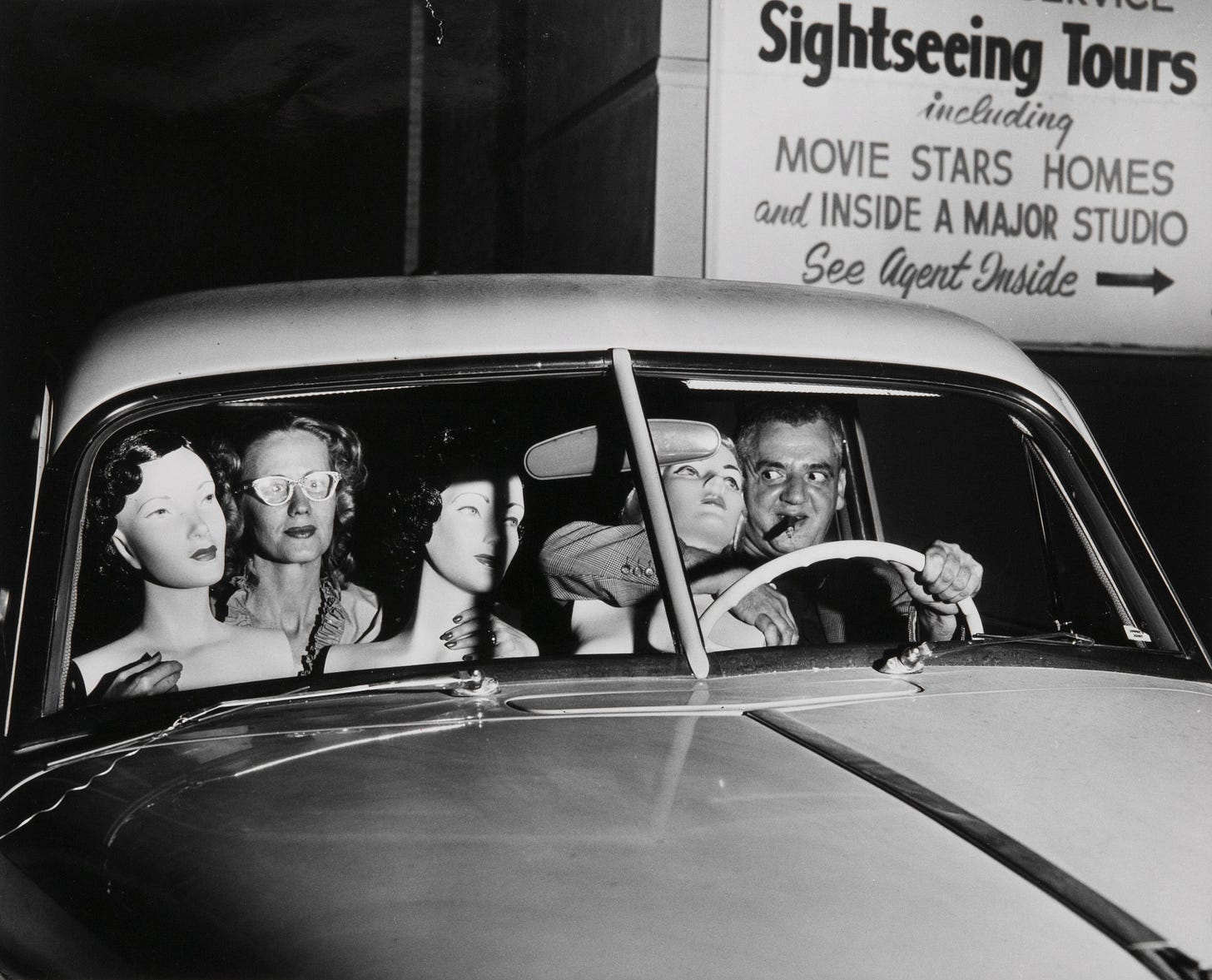

Window displays not only did not move, but they also looked fabulous. As Hellman explained, they “offered a ready-made picture opportunity for the roving street photographer.” So when the French flaneur Eugène Atget roamed the streets of turn-of-the-century Paris with his large-format camera, he set it up in front of corset purveyors and men’s tailors. Later, Walker Evans stalked Depression-era New York City with his Leica, shooting second-hand shop windows crammed with endless curios. Pretty much all the great “street photographers” — Robert Capa, Inge Morath, Elliott Erwitt, Berenice Abbott, Lisette Model, Weegee, Lee Friedlander — would take pictures of shop windows, or people looking at shop windows, or at the very least the city reflected in shop windows.

This is because — beyond practicality — if a documentarian who wanted to capture the soul of his or her city, of his or her society, he or she raced to its shop windows, where le tout de monde gathered to gawk at the artistry and objects on display. The rise of the point-and-shoot camera coincided with the arrival of the large plate-glass window, which allowed retailers to show off their available merchandise (now plentiful thanks to the invention of the sewing machine). Big windows meant lavish displays that drew audiences from far and wide — and from all walks of life — to shop, or at least ogle, the banquet of goods. Veteran curator Phyllis Magidson described this revolution in her essay “A Fashionable Equation: Maison Worth and the Clothes of the Gilded Age”:

Thirsting for au courant fashion information without the liability to actually buy, women flocked from all reaches of the city [specifically New York City] to promenade the avenues and experience first-hand the splendors of store interiors, no strings attached. The attraction of dissolving into the general multitude and anonymously perusing store merchandise proved irresistible to the hoards of fashion pilgrims who flocked to this Ladies’ Mile, so-called for the women it beckoned by providing opulent and safe surroundings. The slackening of former social constraints on unescorted feminine excursions gave birth to newfound mobility for women, encouraging small groups of women to travel together and simply enjoy their leisure experience: New York’s recreational shopper was born.

Initially, these windows functioned as pure advertising, cramming as much merchandise as possible in front of draped cheesecloth or some other backdrop. Virginia Woolf marveled at the array of such dizzying arrangements in London’s Regent Street in 1920, writing in Women’s Leader: “One might string substantives and adjectives together for an hour without naming a tenth part of the dressing bags, silver baskets, boots, guns, flowers, dresses, bracelets and fur coats arrayed behind the glass.” (Window-shopping consumes Woolf’s letters and novels: The Waves, Night and Day, and Mrs. Dalloway all contain vivid descriptions of shop windows.)

Between the 1910s and 1930s, shops began hiring artists to transform their jumbled showcases into full-blown spectacles: museum-worthy tableaux revolving around a specific theme or trend. Macy’s recreated a seaside promenade off the French Riviera, and at Marshall Field’s Arthur Fraser amped up a selection of classical empire-waist dresses by placing them in front of Grecian-inspired statuary and architectural columns. These extravaganzas offered shoppers fantasies in which they could escape into the alluring “romance of Merchandise and Merchandising,” as the one-time window-dresser (and later children’s-book author) L. Frank Baum described it.

Baum, in his various writings as an editor for the magazine The Show Window, championed the use of mannequins — the more voluptuous, the better. (Sex sells.) At first, window dressers used headless forms to showcase a shop’s threads. By the turn of the 20th century, however, these 300-pound iron-limbed dummies came with done-up wax heads, complete with glass eyes, painted faces, and real hair. (Unfortunately, these specimens melted under the bulbs that illuminated their displays. Imagine the horror when one window dresser arrived at work to find the dinner scene he had so meticulously arranged the night before ruined by a party of melting torsos slumped over their wine goblets!)

Manufacturers eventually offered papier-mâché and plaster mannequins, which could withstand the heat from increasingly powerful lights and be manipulated into more naturalistic, dynamic poses — lounging on a sofa or swinging a tennis racket. As the 1920s roared in, mannequins (like their real-life counterparts, who had shed their corsets to embrace a more boyish silhouette) grew sleeker and more stylized: modernist flapper figures with Kohl-rimmed eyes and elongated Modigliani necks.

Mannequins continued changing to reflect society’s (and retailers’) shifting ideals: from stacked knock-outs to girlish waifs — or from blank-faced dummies onto which customers could project their own selves, to expressive dolls with their own unique personalities (some based on real-life VIPs).

In 1928, Pierre Imans introduced a collection of plaster specimens modeled after tennis stars Suzanne Lenglen and Helen Willis, silent film auteur Charlie Chaplin, and nightclub sensation Josephine Baker. In the 1930s, Lester Gaba sculpted Marlene Dietrich and Greta Garbo lookalikes — and created a line of sophisticated-looking “Gaba Girls” based on real New York socialites, including one who appeared on the cover of LIFE magazine. But in 1966, a British designer named Adel Rootstein launched her Twiggy mannequin, which mimicked the model’s petite 5-foot-5-inch frame, expressive doe-like eyes, and cropped hair style. It caused a sensation. Rootstein — and others — scrambled to create other celebrity mannequins, from Donyale Luna and Jerry Hall to Cher and Joan Collins. Imans’s famous mannequins represented novelty more than anything else. Gaba’s didn’t so much recreate real-life glamour gals like Garbo as distill their essence and general vibe. Rootstein, however, made the mannequin the star of the show window — she intuited that pedestrians would respond more to a familiar face of a supermodel or actress than to a gorgeous dress on an anonymous form, no matter how impressive the garment or the backdrop. Her mannequins sold celebrity, or the dream of celebrity, rather than whatever dream or world the designers wanted to sell.

Not every designer or dresser wanted their threads (or inventive scenes) upstaged by a celebrity mannequin. Victor Hugo (the 20th century Venezuelan artist, not the 19th century French novelist) preferred ageless, faceless specimens for his controversial window displays at Halston’s Madison Avenue store. “It would be awful if I had to use mannequins with faces,” he told Hartman for her 1980 book Birds of Paradise: An Intimate View of the New York Fashion World, “because they either look like prostitutes off Forty-second Street or bland models.” And in the 1990s, minimalist designers such as Giorgio Armani preferred personality-less mannequins to better showcase their clean, unfussy clothes. Yet nowadays, as consumers increasingly buy everything off the Internet, shops need to pull out all the stops to get people to go into their stores and buy something. Celebrity has overshadowed every aspect of life. It’s no longer about the clothes.

Then again, for photographers documenting the shop windows throughout the years, it was never really just about the clothes. Eugène Atget took pictures of shops because he wanted to document Paris’ old architecture before modernization took over and destroyed it. His photos depicting rows of limbless torsos and painted disembodied heads have a disconcerting, surrealist, otherworldly quality, tinged with sadness. Walker Evans seemed to delight in the surprising visual juxtaposition of objects and signs one could find in a little downtown shop window, like a sleek porcelain head sandwiched between two old kitchen appliances. Weegee — famous for his gritty street scenes and crime photos — exposed these fancy facades as hilariously grotesque shams, photographing a creepy bald mannequin who had fallen over her broken window display or a group of armless naked statuettes sporting silly hats and high heeled shoes. Lisette Model — a woman, it’s important to note — captured the seductiveness of these displays, how they could actually entice someone to buy, or dream of buying, the goods they’re selling, even if the fur coats and high heels in her windows are partly obscured or blurred. (In one photo she includes a reflection of her manicured hand in the shop window, a tender gesture that connects her, even if in just the smallest way, with that world of fantasy and beauty.)

Lee Friedlander has photographed shop windows since the 1950s and has a book on them, called Mannequin. He is clearly fascinated by these sleek plastic models, but also distrustful of them. His cacophonous photos — which feature shadows and reflections that sometimes cut up the mannequins’ bodies in intriguing ways — highlight the uncanny weirdness of these shapely icons of sex and glamour and capitalism.

Hartman’s mannequin pictures also include reflections and shadows to create striking graphics, visual jokes, and moods. Her best images include glimpses of the world outside: towering modernist buildings, solemn gothic cathedrals, the blur of taxis, rows of scaffolding, street lights, art deco signage, her own reflection. Some are witty. A mannequin in a gold fringe dress dances under a reflection of an American flag. A gorilla grasps two exuberantly dressed dolls and looks ready to scale the building reflected from across the street. Yet unlike Friedlander, Hartman does not use these reflections to undercut the magic of these window displays. She uses them to enhance them and to show how connected, how in conversation, these windows are with the rest of the city — how attuned they are to the populace’s dreams, desires, and flights of fancy.

Hartman knows firsthand the kind of artistry, thought, and genius it takes to conjure these glittering displays. Birds of Paradise, her first book, included a section on how shops sell a designer’s vision through stunning window displays. She interviewed department store heads, mannequin manufacturers, artists, and designers and detailed the infinitely complex process — displaying a keen awareness of how lighting, props, clothing, and set design work together to create a compelling scene:

Just as lighting creates starling effects on a theatrical stage, it can work equal wonders in a window. A display director hires skilled electricians to create an atmosphere that complements the clothes being shown; blue light generally flatters daytime garments, whereas pink light adds a romantic glow to evening fashions. Special templates attached to projectors can simulate shooting stars, a snowfall, a hot sun, and other special effects, while pinpoint lighting (or spotlights) emphasizes a jewel, the cut of a shoe, or a stylish sleeve. Color is equally important; a designer familiar with its psychological effects uses the appropriate shade to produce a desired mood—green for relaxation, red for excitement, blue for serenity, yellow for gaiety.

To Hartman, these windows aren’t just intoxicating advertisements, but works of art. Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, and Salvador Dalí all created imaginative window displays. Even Hugo — whose outrageous windows at Halston included graphic recreations of the Patty Hearst trial, the LaGuardia Airport bombing and a woman giving birth — took this responsibility extremely seriously. He called his vignettes not just displays, but “weekly paintings.”

Hartman thought she had wrapped up her mannequin project in late 2019, early 2020. Then the COVID pandemic hit. Seemingly overnight, all of New York City shut down. Offices closed. Schools closed. Museums closed. City dwellers had to wear masks and stand six feet away from one another. Ambulance sirens blared all day and all night.

The stores closed too, but they did not paper over or pack up their window displays. In a deserted, dissipated New York, these lavish scenes became beacons of joy and hope in a city ravaged by illness and disconnection.

Hartman — with no parties to go to, no galas or events to attend — continued walking the streets and continued to look for beauty. And she found it reflected in the windowed magic of Saks, Bergdorf’s, and beyond. Her photos took on a new, powerful resonance. Though cable news and tabloid papers declared New York dead, her images told a very different story. They showed a city where people still had dreams and desires, where cars still zoomed and commuters still strutted and lights still brightly dazzled. Hartman’s mannequin photos do not capture these elegantly-dressed glamazons posing in a vacuum, but engaging with and responding to the city around them.

That Christmas of 2020 — eight months into a pandemic that would claim more than 1.2 million lives in the United States — designers, carpenters, technicians, and artisans masked up and went to work crafting the city’s spectacular holiday windows. They toiled day and night to produce displays that would delight and comfort New Yorkers battered by the pandemic. These lavish scenes felt — not only in the age of COVID, but at a time when so many brick-and-mortar stores had shuttered — like a dreamy diversion, but also like sustenance, nourishing our eyes and spirit.

Hartman was there to document it all. Like Cartier-Bresson with the instinct to catch “the decisive moment,” she did just that.

If you’re interested in contacting Rose, she asked me to include her email address: rhartmanphotos@me.com. She’s looking for a publisher!

FAntastic article...Thank you

I love this - such an interesting take on how merchandising is a true reflection of the life around it. The photos are so layered and wonderful...